I've been thinking a bit about the strengths of video games as a medium, as well as why I'm drawn to making them. One colors my perception of the other I suppose. But in my estimation every medium has its primary strength.

Literature excels at exploring the internal (psychological, subjective) aspects of a character's personal experiences and memories.

Film excels at conveying narrative via a precisely authored sequence of meaningful moments in time.

And video games excel at fostering the experience of being in a particular place via direct inhabitation of an autonomous agent.

Video games are able to render a place and put the player into it. The meaning of the experience arises from what's contained within the bounds of the gameworld, and the range of possible interactions the player may perform there-- the nouns and the verbs. Just like in real life, where we are and what we can do dictates our present, and our possible futures. Video games provide an alternative to both the where and the what of existence, resulting in simulated alternate life experiences.

It's a powerful thing, to be able to visit another place, to drive the drama onscreen yourself-- not to receive a personal account of someone else's experiences, or observe events as a detached spectator. A modern video game level is a navigable construction of three-dimensional geometry, populated with art and interactivity to convincingly lend it an identity as a believable, inhabitable, living place. At their best, video games transmit to the player the experience of actually being there.

Video games are not a traditional storytelling medium per se. The player is an agent of chaos, making the medium ill-equipped to convey a pre-authored narrative with anywhere near the effectiveness of books or film. Rather, a video game is a box of possibilities, and the best stories told are those that arise from the player expressing his own agency within a functional, believable gameworld. These are player stories, not author stories, and hence they belong to the player himself. Unlike a great film or piece of literature, they don't give the audience an admiration for the genius in someone else's work; they instead supply the potential for genuine personal experience, acts attempted and accomplished by the player as an individual, unique memories that are the player's to own and to pass on. This property is demonstrated when comparing play notes, book club style, with friends-- "what did you do?" versus "here's what I did." While discussing a film or piece of literature runs towards individual interpretation of an identical media artifact, the core experience of playing a video game is itself unique to each player-- an act of realtime media interpretation-- and the most powerful stories told are the ones the player is responsible for. To the player, video games are the most personally meaningful entertainment medium of them all. It is not about the other-- the author, the director. It is about you.

So, the game designer's role is to provide the player with an intriguing place to be, and then give them tools to perform interactions they'd logically be able to as a person in that place-- to fully express their agency within the gameworld that's been provided. In pursuit of these values, the game designer's highest ideal should be verisimilitude of potential experience. The "potential" here is key. Game design is a hands-off kind of shared authorship, and one that requires a lack of ego and a trust in your audience. It's an incredible opportunity we're given: to provide people with new places in which to have new experiences, to give our audience the kind of agency and autonomy they might not have in their daily lives; to create worlds and invite people to play in them.

Kojima has said that game development is a kind of "service industry," and I think I know what he means. It's the same service provided by Philip K. Dick's Rekal, Incorporated: to be transported to places you'd never otherwise visit, to be able to do things you'd never otherwise do. As Ebert says, "video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control." I'll not be the first to point out that this is an astute observation, and one that highlights their greatest strength: video games at their best abdicate authorial control to the player, and with it shift the locus of the experience from the raw potential onscreen to the hands and mind of the individual. At the end of the day, the play of the game belongs to you. The greatest aspiration of a game designer is merely to set the stage.

[This post was referenced in Jonathan Blow's talk "Games Need You" at this year's Games:EDU South conference in Brighton, England.]

7.27.2008

Being There

7.13.2008

Japanese: redux

Happy news!

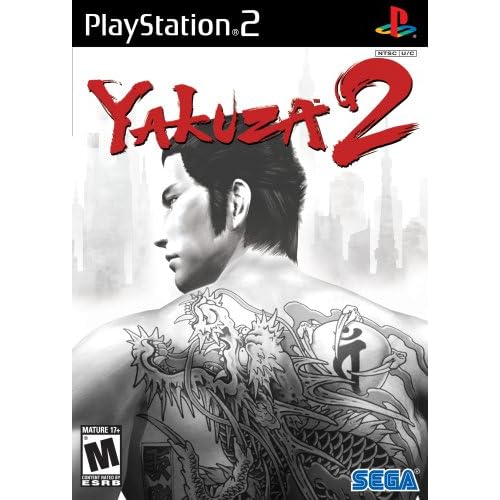

Some time ago, I wrote of my disappointment that Sega was replacing the Japanese voice track in their North American release of Yakuza with a Hollywood voice cast. I ended up playing the full game eventually and did find navigating the world of Yakuza engrossing, but the incongruous voice track left a tarnish on the experience overall.

So, I was excited to read in the current issue of EGM (verified by Sega's official product page) that Yakuza 2's North American release will feature the original Japanese voice track with English subtitles! My guess is that the decision was less artistically-minded than simply pragmatic: I assume that the investment in an English voice cast for the first game didn't pay significant dividends, and with the sequel landing well into the PS2's final hours (not to mention the niche appeal of its subject matter) it's pretty much guaranteed to sell modestly at best. So, market forces and artistic cohesion happen to coincide here, with the most economical production approach resulting in the best end-user experience. Cool. I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

7.06.2008

Stubborn

Via a link on Jonathan Blow's blog today, I played through lo-fi indie game Flywrench. My clear time was 01:02:53. Which is kind of a miracle, and highlighted something odd about 'hardcore' gamers: we can't help but show computers who's boss.

It's weird! Flywrench is a sadistically difficult game, requiring perfect timing, some luck, and a whole lot of patience. To its designer's credit, the game allows you to instantly retry each time you fail, and fail I did-- hundreds of times certainly within that hour and two minutes, sometimes with infuriating frequency.

But I pushed on, determined, for some reason, to best the machine. The game is balanced and designed well enough that each time I failed, I acknowledged that it was my own fault-- my keypress wasn't precise enough, my analysis of the playfield's current state wasn't accurate enough, my understanding of the physics simulation wasn't clear enough. Each time I failed, even as the droning, dissonant soundtrack squealed in my ears, daring me to quit, my determination to master the inputs and pass the game's challenges grew.

And after an hour and two minutes of frustration and anxiety interrupted occasionally by glimpses of elation, I'd achieved what? I saw the credits. I received a readout of my completion time. I got an error message upon trying to close the executable. And it was over.

The graphics were sterile and abstract, functioning only on the symbolic level. The narrative was mildly surreal and led up to a kind of clever joke, but wasn't even a factor in why I was playing. It was the implicit challenge: man versus machine, me versus a digital, unknowing system of rules that didn't care whether I played it or not. But I had to finish the game, practically out of spite. I was proving to the game itself who was boss, or I guess in actuality I was proving to myself that I could do it. Because really, it was just between me and a bunch of numbers. Intellectually, I know that the game was tuned by a person to be just difficult enough to egg me on, but not quite to the point of being impossible. I was being manipulated. And it worked. I wasn't going to let this game kick my ass.

It's so absurd, I don't even know where the compulsion comes from! It's finishing Super Mario Bros. alone in your room at age 8, or completing some punishing, poorly-designed Sierra adventure on your IBM compatible, or 100-percenting Through the Fire and Flames on Expert. It's beating Contra without the 30 lives code, getting to the kill screen on Donkey Kong, finishing a Metal Gear Solid game without being detected, beating Ninja Gaiden on its hardest difficulty setting (or hell, beating the NES version at all,) or completing The Legend of Zelda without picking up any heart containers.

I can see it from the uninitiated viewer's perspective: why do you put yourself through all this anguish just to complete a video game? It doesn't sound like you're having fun. What's the point? Nobody's going to give you a medal, and it's sure not helping cure cancer. Don't people play games to relax?

I don't have a good answer. I don't know why, when this dumb little game pushed me down and stood over me, squelching its little noises and sending me back to the start of the level, I kept getting back up and trying again. But I did it, and I showed the program I'm better than the best it had to offer.

Why do we feel the need to beat the game? Because it's there.

Call to Arms entry 14: Peace

Animator Christiaan Moleman submits a series of interactive vignettes to the Call to Arms, a selection of ground-level perspectives on the conflict in Gaza.

Call to Arms 2008 - “Peace”

A game of interactive vignettes set in and around Gaza, showing several different non-chronological perspectives in 1st person, not unlike Call of Duty 4: a Palestinian child throwing rocks at a tank, an Israeli soldier on patrol, a paramedic, a Western journalist, and others…

It begins and ends with a suicide-bombing in a cafe. The first time you are a mother with her daughter. The second time, you are the suicide-bomber. Cut to black at the crucial moment, or fade if you walk away.

Open on a crowded cafe. You are sitting in a wooden chair on the far side of the room, sunlight hitting the checkered floor through the door behind you. Still morning. You gently sip your coffee. Next to you is a little girl playing with the ice cubes in her empty glass. With the glass in her hand she looks up and smiles.

You pat her on the head.

There’s a half-eaten sandwich on a plate in front of her, with little teeth-marks.

You gesture towards her to eat the rest of it. Reluctantly she takes a bite.

She freezes. When you turn to follow her gaze and look behind you, you see a man enter the cafe. In his hand is a small device. You turn to your daughter and hold her. The man screams something.

CUT TO BLACK

Putting the player in the shoes of different characters might inspire some empathy for the people actually living through this conflict and reflect on the grief it causes to both sides.

Gameplay varies with each perspective: mother interacts affectionately with her little girl, kid tries to throw as many stones as possible without getting hit by stray bullets, paramedic tries to keep a bombing-victim alive for the duration of an ambulance ride, soldier explores cautiously, journalist tries to get coverage of a shoot-out without getting killed, and so on…

Would be a fairly linear affair, with specific interactions up to the player. There should be choice when it matters, but never transparently so. The player should do what he thinks he has to within the confines of the game mechanics rather than press A for ending 1…

The game should be no more than 30 to 60 minutes long so as not to diminish its impact. The Nintendo Wii could be a good platform as it’s shown itself well-suited to extremely varied interactions, though more conventional control-schemes could also apply and some degree of production value would be necessary to sell the character empathy.

--Christiaan Moleman7.02.2008

Conservatism

According to Eurogamer, "Fallout man" Ashley Cheng (allow me to introduce myself, I'm "BioShock man" Steve gaynor) has asked forgiveness for saying in his personal blog that he's disappointed that the design of Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2 look "conservative."

It's one sad-ass day when somebody has to present a mea culpa for calling a spade a spade. The low-level mechanical changes and additions might be debated by hardcore fans, but to the uninitiated viewer, Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2 are outright continuations of the same 2D isometric games I was playing in high school. They might have smoother gameplay, the character models and environments may be rendered in three dimensions and have fancier particle effects, but on an experiential level these are games expressly for the existing fanbase: safe, predictable qualitative refinements in mechanics and presentation, the most conservative possible approach.

The funny thing is, the closest comparison to this situation that I've considered is the game Cheng is currently working on: Fallout 3 could have taken an incredibly conservative approach if it had gone into production as the isometric-3D direct continuation of Fallout 2 that was once under development by Black Isle. That might have satisfied the entrenched, but I'm personally glad to see Bethesda's Fallout 3 trying to create a new, different, more personal experience out of the Fallout universe. How successful any of these projects will turn out is yet to be seen, but I know which has piqued my interest, by virtue of eschewing conservatism.

7.01.2008

Call to Arms entry 13: Fruit of the Womb

Roberto Quesada submits a Call to Arms entry which challenges the player to balance human relationships and material success in a world over which he in fact has very little control: the monopolistic corporate stage of the 19th century.

Starting a new game brings the player to a standard character creation screen: The player chooses what the character looks like, and a certain amount of points will be alloted for distribution amongst various attributes (intelligence, charisma, et c.) and skills (dueling, culinary sauces, et c.), with the distribution of points among the former affecting the weight of points distributed among the latter. The actual attributes and skills present in the creation menu are not important; any game play that would ordinarily depend on these variables will be almost exclusively real-time and depend on the player's own skill, but this will not be made apparent in any way.

After the character is created, the player will form a backstory and mission statement of sorts. The formulation of a backstory depends on the player choosing from various items that make up the history of the family business. All elements here will be generic in nature; for instance, instead of choosing “You're the heir to a steel company,” the player chooses from options such as “You're the heir to a knick knack company.” The instruction manual (or contextual pop-ups) will detail certain aspects of “knick knacks” and “doodads” in an effort to mislead the player into thinking there are nuances that do not actually exist in the game (a history of the materials, a technology tree, popularity of certain items among certain demographics); in reality the way certain products behave or perform will be set mathematically by the game as it progresses (see below). The backstory will also consist of how the family came to its position of power, among other such details, leading the player to believe these variables will affect game play (they most certainly will not).

The mission statement will have a “significant” bearing on game play, as it will be the framework by which the player's “success” is calculated. As part of the process, the player will choose what he most wants to accomplish from goals such as influence, wealth, and notoriety. All goals will be interconnected; the player chooses what he cares about more, with a limited number of things-you-care-about points available for distribution, and the scale created will affect a successometer viewable during game play.

In terms of actual game play, Fruit of the Womb is more or less a sandbox game. It can be first- or third-person, the player interacting with the environment by means of a hand cursor, à la Black & White or that one game that's very dark and requires you to walk around with a flashlight and search through desks. The player has a job as the head of his company, but can delegate nearly all related tasks due to seniority. On the other hand, he has a son or daughter who can be similarly micromanaged or ignored. There is a base level of wealth below which a player can never fall; insuring the funds necessary to delegate the raising of his son: private/boarding school, au pair, military school, whatever. The son's regard for the player/father depends largely on how he is raised, but it is not mechanical or predictable (see below). The player can also directly raise the son by taking time off from work and interacting directly. Via the cursor, the player can smack around or reward his son as he sees fit. He can take his son hunting, or to the zoo, or to a prison for a Scared Straight!, 19th Century Edition-style education. The idea is to give the player ultimate freedom, the likes of which it would be burdensome to describe here, without straying too far from the son/business focus of the game; i.e., the player can somehow be artificially bound to these aspects of game play, but within them he is totally free: if he wants to go downstairs while at work and shoot his accountant in the face, such is his prerogative, though realistic consequences would follow. The player's actions in life will also affect how he is perceived by his son.

In addition to misleading the player with regard to basic gaming conventions, the way the business world and the player's children behave are somewhat randomly determined at the start of the game, with smaller variations occurring as the game progresses. Business trends will follow random occurrences in the game's history, but in an unpredictable way. And when the player's wife pops out a child, the child's personality is randomly defined within the bounds of a loose algorithm created to keep the child's behavior within the realm of reality. The personality will determine how the child responds to being sent to a military academy as opposed to being coddled: will he resent his father more for perceived neglect or for being raised as a nancy boy without the skills necessary for running the family business with an iron fist? There is no way of knowing anything until a route is tried.

The player can also have daughters. Daughters may be groomed in the exact same fashion as sons, but are much more difficult to maneuver into a position of respect within the company as per the societal norms of the proposed historical period. The more children the player has, which is mainly limited by a nine-month gestation period, the more people are vying for power within the company (or not giving a shit, depending on their personalities); this can lead to anything from productivity among the more sycophantic children to patricide. If a player has too many children (the cap is random, within a realistic range), his wife will die, and he will have to engage in a courtship mini game to find a new wife. The wife is little more than a child factory for the player, in an effort to focus the player's affections on his children and business; some wives are stronger factories than others. It's likely that the maximum-children-possible route would never be followed, except for a hearty laugh.

Players' characters grow old and die. The player can then watch time unravel either in real or accelerated fashion. This will allow one to see how things play out indefinitely; though the era never actually changes, the children eventually have their own children, grow old, and die; the player can see how his family and business change. The player is not allowed to continue (“reincarnated” into one of his children, for example) in order to give his actions more weight. He can only start over.

The reasons for the game's unpredictability and sociopathic treatment of the player with regard to his expectations are: 1) To mimic real life and 2) To jar the player. Ideally a game like this would be extremely complicated (on the level of a detailed MMORPG's mechanics, for example, if not greater) in an effort to dissuade the player from attempting to play the game how it “ought” to be played by attempting to max out the successometer, but not so complicated that the player couldn't come up with methods for “success.” This is probably unachievable, but the idea would be to give the game a level of complexity that would require the player to play constantly and attentively (taking his own notes, as the game will not have an automatic notepad or “journal” feature) if he wanted to have success in the manner that the game apparently requires; the game would be tedious and life-ruining but “winnable,” or interesting/entertaining (hopefully) but rewarding on a different level. Note that disregard for the successometer does not mean complete disregard for the business; the player can still groom his son to take over, but just not worry about whether the son will preserve the family legacy to a T. The successometer does not punish, but merely exists. The player can follow his initial expectations or eschew them.

The main theme being explored here is how one's sense of duty forms. The player is deliberately put into a game with certain expectations in an effort to mimic the social stressors that existed in the era; does the player comply merely because there exists an order that the game wants him to follow, or does he ignore the game and form a bond with his child(ren)? Following what's expected is tedious (though maybe not for all people) and results in a gauge filling up; the player can be rewarded with some sort of tokens or with the unlocking of business opportunities the more he keeps his “success” level high. Or does the player pursue a familial relationship with no apparent reward save the relationship itself? Characters would have to be realistically rendered, or at least have realistic responses/emotions, in order for the player to feel some sort of empathy, but pursuing this route, which again would not be presented overtly by the game as a possibility, could unlock more depth to the relationship aspect of the game, making the bond more meaningful as the player pursues this route.

Concerns:

1. Perhaps only a small set of people could actually empathize with the characters of a video game.

2. If this game were made, the concept would eventually be leaked (possibly before the game is even released), in effect making the game meaningless.

3. Misogyny.