Lots of people do end-of-year lists. In considering throwing my hat into the ring, I started putting together a list of my favorite games of 2008... and then realized that gaming for me this year wasn't defined by individual titles, but by memorable moments from lots of different games (and that some games which were very memorable for me would've been sadly disqualified from my 'favorite games of the year' list.) So, what follows is my gaming "Moments of the Year 2008." Note that this includes any games I've played for the first time this year, so 2005's Haunting Ground makes the cut (it was new to me!) while my ~12th playthrough of Full Throttle does not.

Note that these items may contain spoilers for the games involved. The list, in completely subjective order:

Gloriously, Fallout 3 is by-and-large the sum many small, free-floating story nodes, gathered at will by the player into a matrix of experience unique to oneself. A few of these nodes stand out especially strongly: deciphering what transpired in Vault 106; happening upon the hidden vault where Dad is holed up; following a lost android's trail from a holotape in Moira's shop all the way to Rivet City; but most memorable among them must be Agatha's Song, a quest which combined subtle but evocative fiction that emphasizes the way the world has changed after the bombs dropped, with a simple but incredibly affecting reward that changes your ongoing experience of the wasteland. The Soil Stradivarius, what would be a priceless museum piece in today's world, has had its value transmuted to the purely sentimental. Searching for it draws you into the tragically inhumane story of Vault 92's downfall, and completing the quest doesn't save the world, or even any lives; it only reunites a lonely old woman with a bit of her family's history. Upon completion, the player gains Agatha's radio station, her violin-playing lending the wasteland a new, haunting dimension. Immediately after I completed the quest, I left Agatha's house and walked to a nearby ridge. Carrion birds were lazily circling over the valley. I knelt there for quite some time, listening to the strains of Agatha's violin and watching the birds' black silhouettes dance against the setting sun.

It's the little things that count. And within the first hour of big-budget FPS Far Cry 2, I experienced a little thing that felt like a big deal: I stood in front of a door, reached my hand out, grasped the knob, and opened it. By god, it's like a revelation. After years of opening doors by proximity, of pressing buttons with my mind, of picking up items by looking at them, I actually had hands, and they touched the world, and the world responded. Yes, it's all a scripted hand- and camera animation; it's no Trespasser hand, you really just click the door and a tiny authored in-game cinematic sequence occurs. But forget the specifics, it's the sentiment that counts: I'm a person, I'm there, I exist in this gameworld and I have to open doors just like any real person would. These are the same glimmers I spotted when playing Hitman: Codename 47 for the first time, and seeing Agent 47's hand flit out to individually pick up each ammo magazine off of a table; the same when the protagonist of Crysis reaches out to grab items from the world; the same when Jackie Estacado dynamically maneuvers his guns around the edge of a wall. It's a touch of simulational veracity-- of physicality-- that may throw other conceits into sharp relief (I still automatically absorb fallen enemies' ammo by stepping on their guns?) but nonetheless creates a meaningful impression of being there in the moment.

Though Resident Evil 5 won't be available until next year, the Japanese version of the Xbox 360 demo could (for a time) be loaded onto Western consoles. I was lucky enough to play it when one of our QA footsoldiers brought the files in on disc, and the first few playthroughs of the demo's two scenarios presented some of the most dynamic, vital co-op action I've ever played. The sequences where the level's space opens up-- the second half of each scenario-- allowing the players to run for cover, climb on roofs, jump through windows, flank, assist, hide, and generally own the entirety of the space while a hulking freak and his mutated honor guard bear down on you were just incredibly expressive, and genuinely thrilling and frightening at the same time. This isn't the dark, desolate, lonely fear of Resident Evil 4-- the designers, knowing co-op would inherently lend levity and energy to play, set the game under the bright African sun. This is that "oh, shit, he's right behind you!" "run, run, run!" "help me, he's got me, oh god!" kind of fear that perfectly complements the presence of another player. Tactics were devised, uppercuts dished out, and triumph achieved. The incredible micro-drama of each playthrough, and the players' autonomy to mold their presence in the space to their own playstyle, is worlds beyond the limited options and plodding advance through a typical cover-based stop-and-pop'em-up; it's a co-op shooter experience that feels, surprisingly, like something entirely new.

While much of Haunting Ground is compelling for its oppressive atmosphere-- the demented nature of the castle, the feelings of helplessness and vulnerability inherent to inhabiting the game's defenseless female protagonist, the abiding uncertainty about your captors' intentions-- the game is at its best during the apex of its first half, AKA "the good part." I've written at length about the game already, but I'll note that it's worth completing Daniella's chapter for the visual poetry of her demise, and the sense of satisfaction at besting the game's most poignant rival. Just do yourself a favor and pretend the game ends then and there.

There's nothing I like more than character customization, when it comes right down to it. And while there was much to love about No More Heroes-- chronicled in detail here-- I derived endless enjoyment from dressing up Travis in more and more ridiculous shirts (designed by game director Suda 51 himself under the pseudonym "Mask de Uh) found in dumpsters throughout Santa Destroy or bought from the local punk clothing outlet. My favorite had to be the one featuring the text "CAT FIGHT" in rounded pink letters, accompanied by a cuteoverload.com-worthy portrait of a fluffy white cat. To know that Travis's absurd appearance was my fault as he hacked through endless, bloody waves of enemies made the proceedings that much more enjoyable-- the personal touch that makes the experience yours.

I'm not a big indie gamer, I admit it. And I'm not often one for strictly challenge-based, mechanical gameplay. But Flywrench, much like God Hand (a very different game, to be fair,) was so pure, such a precise and finely-tuned unforgiving machine, that I was compelled to live up to its standards, and become a good enough player to complete it. Like Clover's beat-em-up, Flywrench is brutally difficult, but not cheaply or unfairly so; quite the opposite, in that every time the player fails, he knows it was his fault alone-- for not supplying precise enough inputs, for not maintaining exacting enough timing, for not honing the connection well enough between the game's state and his own fine motor reactions. When I finished the game, I didn't receive the spectacle of a lushly-rendered cinematic or a cache of Gamerpoints; I gained the satisfaction of having stood at the foot of the mountain, and proven I could climb it.

See above under character customization; the inclusion of the weapon upgrade system in Army of Two was a brilliant move. It reinforces the themes of the premise in multiple ways-- as mercenaries, it gives you a reason to want money, and as wantonly uncaring and materialistic mercenaries, it gives you something egregiously destructive and ostentatious to spend your money on. Not only can you upgrade the power and accuracy of each weapon, RE4-style, but each piece of your arsenal can be "blinged" for a flat fee, resulting in gold-plated rocket-propelled grenades, a platinum filigreed magnum so large it requires a foregrip, or an AK-47 covered in rubies and diamonds. The ability to preview each upgrade, and the compulsion to earn enough cash to unlock them for use in the game proper, convinced another designer and I to complete the entire co-op campaign where we otherwise most likely would have moved on much sooner. Respect: as a player retention strategy, this system just made good business sense. Subversion: since the game is in third person, and the pauldrons of your player model obscure your gun in-game, there's no way to look at what you've unlocked on your own-- you have to get your buddy to aim his viewport at your upgraded piece to be able to see it at all. This results in two grown men sitting side-by-side in a dimly-lit room saying, "look at my gun, bro. Just look how big it is. Yeah, zoom in on it. That's good." One more way in which the system reinforces the game's fictional premise.

Once more to the well of character customization, this moment is particularly surreal: I found that Rock Band/2's character creator allowed an eerily accurate recreation of myself onscreen, to the point that anyone who happened by while we were rocking the office after hours would comment on the likeness. So, when it was announced that Harmonix/EA were setting up a service allowing players to order 3D fabrications of their Rock Band 2 avatars from their website, I knew what had to be done. I now possess a 1/10th scale figurine of myself, which sits on my desk at work. The cycle is complete.

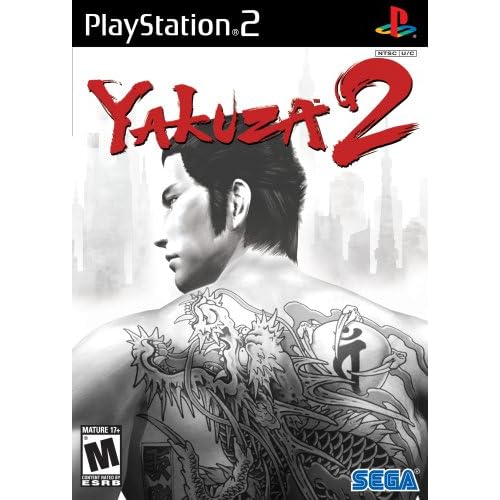

There are a million stories in the naked city, and Yakuza 2 was at its best when it let the player discover them at his own pace. Though the game was chopped up into chapters that were bookended by linear narrative missions, in between the player was free to plumb the utter strangeness of the game's fictionalized modern Tokyo and Osaka, depicted via myriad small, disconnected side-missions and self-contained gameplay moments. While the game's story spine conducted itself with melodramatic gravity, the mini-threads surrounding it were anything but weighty: take joy in hunting down a ballerina's lost slippers (hint: a homeless man is wearing them after finding them on the street;) in judging a young man's amateur rap; in facing off against a diaper-fetishist Yakuza boss and his gang; in helping an amnesiac by clonking his head with a baseball bat; in exposing a fake-pregnancy extortion scam (hint: you've never met this woman before, and doesn't that belly look a bit rubbery?) in solving a friendly busker's congestion problems; in fending off a bosozoku biker gang that's assaulting a host club, and many more unpredictably weird and big-wide-grin-inducing scenarios.A man runs up to you on the street and hands you a "soiled videotape," imploring you NOT to watch it, to throw it away immediately. If you choose to take it to a video booth and watch it anyway, an unsettling image of a woman in a red dress appears onscreen, and the item's name in your inventory changes to "cursed tape." You exit the video booth into an alley, and a man claiming to be an exorcist stops you, warning of a terrible omen he senses hovering over you. You turn him away, but as you step out into the street, you catch a glimpse of a very familiar-looking red dress down at the other end of the block. Do you dare follow?

Despite the game's emphasis on big-budget cinematics and an epic crime tale, it's this matrix of unfettered little stories of the city that was the real heart and soul of Yakuza 2 to me, and what made it one of my favorite games of this year.

As a first-person shooter Turok isn't necessarily exceptional, but as a dinosaur-slaughtering simulator it stands unparalleled. See, Turok is a dinosaur hunter-- one with big burly arms and a big shiny knife. While shooting dinosaurs is technically an option, it's preferable to get within arm's-length of a dino and, with a single, simple button press, watch as Turok absolutely guts his target with mechanical precision. This works on any dinosaur, big or small, carnivorous or harmless, all executed with the same soulless proficiency and seeming disdain toward all of dino-kind. The fact that each dinosaur-stabbing is depicted with the exact same canned animation, and that in high-dino-density situations these stabbings can occur in rapid succession, delivers an image of Turok as unfeeling dino-slaughterhouse worker, numbly snuffing out tiny life after tiny life, then "throwing the corpses aside like worthless garbage," as one co-worker put it. The greatest moment must have been when I ran up on a scripted sequence of four velociraptors attacking a defenseless parasaurolophus: bypassing the pack of predators, I homed in on the harmless plant-eater, casually jamming my knife into its throat like a basketball player delivering an easy layup. Ah, Turok. What a genocidal asshole you are in my hands.

In both scope and fidelity, it's safe to call GTA4 an epic production. And really there was no better investment made than their decision to embrace Euphoria character physics. This technology (which I don't pretend to understand well) allows characters to inhabit a state somewhere between posed and ragdolled, resulting in incredibly convincing tumbles off of motorbikes and through windshields, as well as wonderfully physical reactions by civilians to being pushed, bumped, and generally manhandled. Nowhere is this better showcased than in the game's implementation of a drunken state: Nico and his drinking buddies stumble, lean, wobble, catch themselves, trip and fall with amazing dynamism, fully expressing a feeling of being out of control of one's own body, and providing enormous comic relief as well. One particularly memorable moment was when Dwayne and I both tumbled down a flight of stairs into an alcove, and spent the next five minutes down there falling all over one another, completely unable to navigate the steps back up to street level. The image of these two jackasses crawling all over one another, seemingly trying to help each other up but, too bad, the blind can't lead the blind drunk, was simply priceless. My only disappointment was that I don't recall ever seeing drunkards out and about in the city. How great would it be to come across some random civilians stumbling around drunk in front of a bar, and know you were in for a couple minutes of simple fun just making them trip all over each other and watching the ensuing chaos? Much like the earlier entry on Far Cry 2, in a game this big it's often the little things that count.

Have some memorable moments of your own? Feel free to share. Here's wishing you a 2009 filled with these kinds of unforgettable experiences that only video games can provide.

12.28.2008

MOTY 08

12.24.2008

Casting 3

In an attempt to provide coverage over the Christmas break, I recently recorded two podcasts in a row with the Idle Thumbs crew: one is available now, the other should run next week. This week's is a weird one, where we spend most of our time talking about old simulation games and other seemingly (but not!) boring stuff. Also covered: the origins of indie shooter Retro/grade, a city-building MMO, and Emily Dickinson tech demos.

References:

Minotaur China Shop

QWOP

Gamasutra Last Express retrospective

Penumbra

Peter Molyneux's "Emily Dickinson" presentation

SimCity 4: Rush Hour

CitiesXL

Bus Driver

Eric Kaltman's blog

Retro/Grade

12.21.2008

Holiday confab

I appear on the 2008 holiday edition of Michael Abbott's Brainy Gamer Podcast, specifically in "Volume 3" of the series. Abbott asked more than a dozen guests for their favorite games of the year, then brought small groups together to discuss their picks on the air. I was joined by Wes Erdelack of Versus Clu Clu Land and Tom Kim of Gamasutra Radio. It was an interesting chat; I look forward to listening to the rest of the sessions, and hope you will too.

12.14.2008

The Cabrinety Collection blog

Somehow or another I came across this blog today: Eric Kaltman's work cataloging the contents of the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection at Stanford. There are a number of incredibly enlightening posts already, focusing primarily on obscure, forgotten, or otherwise intriguing computer games from the 80's.

According to the site, Cabrinety was a graduate of Standford; a software engineer, entrepreneur, and computer game hardware and software archivist from his teens onward. He died at the early age of 29 (only a few years older than I am now,) leaving his extensive collection to the Stanford University Library.

Kaltman posts more-or-less monthly examining different slices of the collection, such as 80's financial market software, avenues of realistic simulation left by the wayside, the style versus substance of early Psygnosis titles, and more on Nintendo, Sid Meier, and Sierra.

It's enough to make one feel nostalgic for the early, dry, nerdy, wild west days of game development, regardless of how clearly one might remember them.

12.06.2008

Yearbook

Leigh Alexander, video game journalist person and writer of the SexyVideogameland blog, started a side project a little while ago: it's a sort of yearbook of video game developers of all stripes who volunteer to participate, under the (possibly slightly unfortunate) banner of SexyVideogamedeveloperland. I opted in, as have a number of developers from prominent studios like Bethesda, Ubisoft Montreal and Sony, as well as some indie projects, representing programming, design, QA, art, and everything in between.

It's an interesting project, specifically because its main goal is to humanize game developers, who are often obscured behind the monolithic banners of their publishers or development houses. The most useful aspect of this venture as I see it would be the project's potential to inspire. I know that one major step in my own process of realizing I wanted to make games professionally was reading about the few individual figures the games industry made available to fans at that time: Will Wright, Peter Molyneux, Tim Schafer, Warren Spector and others. Seeing that games were made by people, and reading the stories about how they'd gotten to where they were, that they tended to be conversant on games the same way I was, and that this was something that anyone could do if they were willing to put forth the effort, was the inspiration I needed to decide I was going to devote myself to the pursuit of making games.

So, I added a little "how I got into game design" blurb on my post. If some young person reads through the SVGDL entries and it brings them one step closer to joining the game development ranks, I think there will have been a positive effect. The main thing the project needs is more developers getting involved, and more people getting the word out. If you have a minute and the means, jump in!

11.21.2008

The immersion model of meaning

Being There was quoted in Jonathan Blow's revision of his talk "Conflicts in Game Design," which he recently presented as the keynote of this year's Montreal International Game Summit. I'm honored to have one of my essays, which stole most of its ideas from Doug Church, referenced by someone who drives so much discussion in the industry.

Though it was only touched on lightly in his keynote, Blow raised an interesting concern: does abdication of authorship have the potential to convey profundity or deep meaning?

The question begs a definition of "deep meaning." Can such meaning only be derived from a sender-receiver relationship, where the genius author cooks up deeply meaningful thought in his head and hands down his superior understanding to the waiting masses? This is the artistic mode which Ebert relies on to judge traditional media, disqualifying video games from consideration wholesale. And it is this very mode that Blow acknowledges as unsuited to our interactive medium, referring to it as the staid "message model of meaning." He notes that when games rely on linear, Hollywood-style stories, or when art games attempt to convey moralistic platitudes through systemic play, they are perpetuating the message model, and wonders aloud what valid alternatives might be. I would argue that abdication of authorship, when paired with certain existing game forms, points toward such an alternative: a mode that trades painstakingly-paced plot points or densely symbolic mechanics for a matrix of unstructured potential personal revelations; one that trades grand, orchestrated received meaning for the encompassing sensation of visiting someplace outside the player's prior experience, with the potential to return deeply changed. The immersion model of meaning, as it might be called, takes the act of travel as its primary touchstone, instead of relying on traditional media such as film, the novel, or even sculpture, music or painting to inform the author's role.

I would argue that abdication of authorship, when paired with certain existing game forms, points toward such an alternative: a mode that trades painstakingly-paced plot points or densely symbolic mechanics for a matrix of unstructured potential personal revelations; one that trades grand, orchestrated received meaning for the encompassing sensation of visiting someplace outside the player's prior experience, with the potential to return deeply changed. The immersion model of meaning, as it might be called, takes the act of travel as its primary touchstone, instead of relying on traditional media such as film, the novel, or even sculpture, music or painting to inform the author's role.

Consider a trip you've taken to a faraway city or country. You leave your home, arriving in an unfamiliar place, and are set loose in this new context. You are unfamiliar with the layout of the streets or public transportation; the language and customs might be different from your own; even little things like signs indicating a bathroom or payphone may be alien to you. You begin to explore your new surroundings, perhaps guided by a tourist's handbook or a friend who knows the area, and begin mapping this new place into your mind. You meet new people and gain perspective by learning about someone who's known this place their entire life; you discover the history of the place and how it may have impacted the residents. You find out how the person you are changes when introduced to someplace new and strange. And then you return home, bringing a little bit of that changed person back with you. Video games have the ability to provide these new contexts of experience, and maybe to change the people who visit their gameworlds in much the same way. The immersion model of meaning arises from design focus along two primary axes: providing a believable, populated, internally consistent, freely-navigable gameworld for the player's avatar to inhabit, and robust tools of interactivity that allow the player to build a personal identity within that gameworld through his own actions. Video games are already capable of doing these things; they are far less capable of providing the authored pacing, composed framing and predictable event flow of film to convey a linear narrative, and yet this is almost always a central focus in character-driven games. Embracing the immersion model of meaning requires the designer never think of the game as a story, but as a place filled with people and things that the player is free to engage with at his own pace and on his own terms.

Video games have the ability to provide these new contexts of experience, and maybe to change the people who visit their gameworlds in much the same way. The immersion model of meaning arises from design focus along two primary axes: providing a believable, populated, internally consistent, freely-navigable gameworld for the player's avatar to inhabit, and robust tools of interactivity that allow the player to build a personal identity within that gameworld through his own actions. Video games are already capable of doing these things; they are far less capable of providing the authored pacing, composed framing and predictable event flow of film to convey a linear narrative, and yet this is almost always a central focus in character-driven games. Embracing the immersion model of meaning requires the designer never think of the game as a story, but as a place filled with people and things that the player is free to engage with at his own pace and on his own terms.

Using three-dimensional space primarily to convey linear story constrains the high-level experience into two dimensions, and two directions-- forward and back. To paraphrase Blow, this dichotomy is inherently conflicted. Games have the potential to present experience that works like our own world-- where there's no one clear 'path' forward except the one we choose, and one's larger individual story is the sum of many smaller personal ones-- but video games' reliance on linear core narrative funnels the possibility space into one line, one story, that may twist and branch, but that nonetheless serves to homogenize the potential experience across all players who choose to visit your gameworld. Under the immersion model, instead of relying on an authored message encoded in a single traditional narrative stream, meaning arises from the content developers' ambient characterization of the gameworld itself and the non-player characters who inhabit it. Instead of gaining perspective by seeing specific events through the eyes of a particular character, the player gains perspective by himself inhabiting a world apart from his own daily experience and coming away with a sense of meaningful displacement. Content creators still have the immense power to render interesting characters with engaging personalities, behaviors and desires, and to create unique locales with their own histories; the Hollywood screenwriter simply need not apply.

Under the immersion model, instead of relying on an authored message encoded in a single traditional narrative stream, meaning arises from the content developers' ambient characterization of the gameworld itself and the non-player characters who inhabit it. Instead of gaining perspective by seeing specific events through the eyes of a particular character, the player gains perspective by himself inhabiting a world apart from his own daily experience and coming away with a sense of meaningful displacement. Content creators still have the immense power to render interesting characters with engaging personalities, behaviors and desires, and to create unique locales with their own histories; the Hollywood screenwriter simply need not apply.

I've gained unique perspective by engaging with the fictional people and places of recent games: combing the starscape for descriptions of unexplored planets in Mass Effect painted a vision of the fantastic possibilities that might lay beyond our solar system; engaging with the outright gonzo civilians and unstructured side missions of the Yakuza games gave me the feeling of visiting modern Japan through a particularly twisted lens; traipsing about the savanna doing the increasingly grim dirty work of Far Cry 2's procedurally-generated faction representatives conveyed a unique sense of a place in the grip of nihilistic self-destruction; freely exploring the Capital Wasteland in Fallout 3 and choosing to complete unanchored quests like Agatha's Song illustrated just how much our world, and humanity's value systems, might change when faced with global catastrophe. The most memorable stories I recall from these games lay outside the narrative spine; the immersion model of meaning would be best served by a game that had no static central story weighing it down at all, just as our own lives have no predetermined single path. The purest and most unassuming current example of the described approach must be Animal Crossing: it's a highly interactive other place filled with a loosely-arranged rotating cast of quirky personalities, which the player is invited to visit as often as he likes. Engagement with the game comes from the desire to visit this little world, see what it's like, see how it changes with the seasons, how the animals' child-like whims come and go, and how the player is able to craft his own identity within this wonderfully surreal and innocent context. There are elements of progression-- buying a bigger house, filling out the museum's collections, collecting sets of rare items-- but no authored story or mandatory participation of any sort; there is a beginning, when you first step into your town, but no "end" in a traditional sense. It is a pocket world that goes about its own business on its own time, but also responds to any presence the player may have in it. Its message is not inherently grand or profound-- but the experience of having been there creates genuine memories, and points toward a form that holds the potential to foster deep meaning in the individual who chooses to become immersed in it.

The purest and most unassuming current example of the described approach must be Animal Crossing: it's a highly interactive other place filled with a loosely-arranged rotating cast of quirky personalities, which the player is invited to visit as often as he likes. Engagement with the game comes from the desire to visit this little world, see what it's like, see how it changes with the seasons, how the animals' child-like whims come and go, and how the player is able to craft his own identity within this wonderfully surreal and innocent context. There are elements of progression-- buying a bigger house, filling out the museum's collections, collecting sets of rare items-- but no authored story or mandatory participation of any sort; there is a beginning, when you first step into your town, but no "end" in a traditional sense. It is a pocket world that goes about its own business on its own time, but also responds to any presence the player may have in it. Its message is not inherently grand or profound-- but the experience of having been there creates genuine memories, and points toward a form that holds the potential to foster deep meaning in the individual who chooses to become immersed in it. We already build incredible, vivid places, but feel the compulsion to pave over them with our attempts at compulsory pre-authored story structures. In embracing the immersion model of meaning, one's approach would shift away from building games around a core of Hollywood-style narrative, and toward building unique, convincing, open, integrally full gameworlds, populated by intriguing people to meet and things to do, and providing the player with tools of meaningful self-expression within that context that he might return changed by his experiences. Our attempts to bridle the player's freedom of movement and force our meaning onto him are misguided. Rather, it is that distinct transportative, transformative quality-- the ability of the player to build his own personal meaning through immersion in the interactive fields of potential we provide-- that is our unique strength, begging to be fully realized.

We already build incredible, vivid places, but feel the compulsion to pave over them with our attempts at compulsory pre-authored story structures. In embracing the immersion model of meaning, one's approach would shift away from building games around a core of Hollywood-style narrative, and toward building unique, convincing, open, integrally full gameworlds, populated by intriguing people to meet and things to do, and providing the player with tools of meaningful self-expression within that context that he might return changed by his experiences. Our attempts to bridle the player's freedom of movement and force our meaning onto him are misguided. Rather, it is that distinct transportative, transformative quality-- the ability of the player to build his own personal meaning through immersion in the interactive fields of potential we provide-- that is our unique strength, begging to be fully realized.

[Michael Samyn of Tale of Tales has independently posted a piece that I would consider a sister essay to the above-- maybe long lost sisters that grew up on opposite sides of the world only to later meet one another and find out how much they have in common. Please take a few minutes to read this eloquent and concise examination of games, immersion and meaning.]

11.17.2008

Casting 2

I appear again this week on episode 7 of the Idle Thumbs podcast. We wax effusive about Fallout 3, I break Chris's chair, and the phrase "hot scoops" is dropped in excess of 80 times. Enjoy... if you dare!

Click here for Idle Thumbscast!

References

- Illbleed 2nd Trailer

11.02.2008

Muertos 08

It was a year ago tonight that Rachel and I attended our first Dia de los Muertos celebration in San Francisco's Mission district, and we went again this year.

Since my prior post sums up the meaning of the proceedings, I'll just show some pictures from this year's parade.

This parade has become one of my favorite yearly events. The energy and vibrancy of the proceedings are just incredible. Though I got a couple good pictures, they really don't do the event justice. Suffice it to say, it's something worth going out of your way to see in person. I'm glad I could be there again this year, and hope to be there for many more.

10.22.2008

Casting

As a former member of the Idle Thumbs video game website editorial staff, I'm proud to have taken part in Idle Thumbs Podcast 3: Field of Dreams. The episode is now available on www.idlethumbs.net, or through your local iTunes. Come along with us on an embarrassing aural journey, as we lovingly cast our pod into your face. Or don't. That's your call.

10.16.2008

9.28.2008

On Invisibility

Thanks to friend Chris Remo for republishing this essay on the Gamasutra network.

When one is moved by an artist's work, it's sometimes said that the piece 'speaks' to you. Unlike art, games let you speak back to them, and in return, they reply. If the act of playing a video game is akin to carrying on a conversation, then it is the designer of the game with whom the player is conversing, via the game's systems.

In a strange way then, the designer of a video game is himself present as an entity within the work: as the "computer"-- the sum of the mechanics with which the player interacts. The designer is in the value of the shop items you barter for, the speed and cunning your rival racers exhibit, the accuracy of your opponent's guns and the resiliency with which they shrug off your shots, the order of operations with which you must complete a puzzle. The designer determines whether you win or lose, as well as how you play the game. In a sense, the designer resides within the inner workings of all the game's moving parts.

It's a wildly abstract and strangely mediated presence in the work: unlike a writer who puts his own views into words for the audience to read or hear, or the painter who visualizes an image, creates it and presents it to the world, a game designer's role is to express meaning and experiential tenor via potential: what the player may or may not do, as opposed to exactly what he will see, in what order, under which conditions. This potential creates opportunity-- the opportunity for the player to wield a palette of expressive inputs, in turn drawing out responses from the system, which finally results in an end-user experience that, while composed of a finite set of components, is nonetheless a unique snowflake, distinct from any other player's.

One overlapping consideration of games and the arts is the degree to which the artist or designer reveals evidence of his hand in the final work. In fine art, the role of the artist's hand has long been manipulated and debated: ancient Greek sculptors and Renaissance painters burnished their statuary and delicately glazed their oils to disguise any evidence of the creator's involvement, attempting to create idealized but naturalistic images-- windows to another moment in reality, realistic representations of things otherwise unseeable in an age before photography. Impressionist artists, followed by the Abstract Expressionists, embraced the artist's presence in the form of raw daubs and splashes of paint, drifting away from or outright opposing representational art in the age of photographic reproduction. Minimalists and Pop artists sought in response to remove the artist's hand from the equation through industrial fabrication techniques and impersonal commercial printing methods, returning the focus to the image itself, as a way of questioning the validity of personal and emotional artistic themes in the modern age. The designer's presence in a video game might be similarly modulated, to a variety of ends. If a designer lives in the rules of the gameworld, then it is the player's conscious knowledge of the game's ruleset that exposes evidence of his hand.

The designer's presence in a video game might be similarly modulated, to a variety of ends. If a designer lives in the rules of the gameworld, then it is the player's conscious knowledge of the game's ruleset that exposes evidence of his hand.

Take for instance a game like Tetris. Tetris is almost nothing but its rules: its presentation is the starkest visualization of its current system state; it features no fictional wrapper or personified elements; any meaning it exudes or emotions it fosters are expressed entirely through the player's dialogue with its intensely spare ruleset. The game might speak to any number of themes-- anxiety, Sisyphisian futility, the randomness of an uncaring universe-- and it does so only through an abstract, concrete and wholly transparent set of rules. The player is fully conscious of the game's rules and is in dialogue only with them-- and thereby with the designer, Alexey Pajitnov-- at all times when playing Tetris. While the game's presentation is artistically minimalist, the design itself is integrally formalist. But whereas formalism in the fine arts is meant to exclude the artist's persona from interpretation of the work, a formalist video game consists only of its exposed ruleset, and thereby functions purely as a dialogue with the designer of those rules. Embracing this abstract formalist approach requires the designer to let go of naturalistic simulation, but allows the most direct connection between designer and player: a pure conduit for ideas to be expressed through rules and states. Alternately, the designer's hand is least evident when players are wholly unconscious of the gameworld's underlying ruleset. I don't mean here abstract formalist designs wherein the mechanics are intentionally obscured-- in that case, "the player cannot easily obtain knowledge of the rules" is simply another rule. Rather, I refer to "immersive simulations"-- games that attempt to utilize the rules of our own world as fully as possible, presenting clearly discernible affordances and supplying the player with appropriate inputs to interact with the gameworld as he might the real world. Theoretically, the ultimate node on this design progression might be the experience of The Matrix or Star Trek's holodeck-- a simulated world that for all intents and purposes functions identically to our own, and with which the player may interact fludily and unconsciously. This approach to game design bears most in common with Renaissance artists' attempts to precisely model reality through painting, to much the same ends: an illusionistically convincing work which might 'trick' the viewer into mistaking the frame (of the painting or the monitor) for a window into an alternate viewpoint on our own reality.

Alternately, the designer's hand is least evident when players are wholly unconscious of the gameworld's underlying ruleset. I don't mean here abstract formalist designs wherein the mechanics are intentionally obscured-- in that case, "the player cannot easily obtain knowledge of the rules" is simply another rule. Rather, I refer to "immersive simulations"-- games that attempt to utilize the rules of our own world as fully as possible, presenting clearly discernible affordances and supplying the player with appropriate inputs to interact with the gameworld as he might the real world. Theoretically, the ultimate node on this design progression might be the experience of The Matrix or Star Trek's holodeck-- a simulated world that for all intents and purposes functions identically to our own, and with which the player may interact fludily and unconsciously. This approach to game design bears most in common with Renaissance artists' attempts to precisely model reality through painting, to much the same ends: an illusionistically convincing work which might 'trick' the viewer into mistaking the frame (of the painting or the monitor) for a window into an alternate viewpoint on our own reality.

However, where Renaissance artists needed to model our world visually, designers of immersive simulations strive to model our world functionally. This utilization of an underlying ruleset that is unconsciously understood by the player allows the work of the designer to remain invisible, setting up the game as a more perfect stage for others' endeavors-- the player's self-expression, and the writer's and visual artist's craft-- as well as presenting a more perfectly transparent lens through which the game's alternate reality may be viewed. Every time the player is confronted with overt rules that they must acknowledge consciously, the lens is smudged, the stage eroded; at every point that the functionality of a simulated experience deviates jarringly from the natural world's, the designer's hand is exposed to the player, drawing attention away from the world as a believable place, and onto the limitations of an artificial set of concrete rules dictated by the designer.

Clearly the theoretically ideal, VR version of 'being there' is impossible with current technology, and may never become a reality at all. But using the concept of perfectly invisible simulation as a lens for examining player immersion in current games, how do common design conventions of today unintentionally draw the designer's hand into the fore, resulting in more mediated or artificial experiences?

One common pitfall might be an over-reliance on a Hollywood-derived linear progression structure, which in turn confronts the player with a succession of mechanical conditions they must fulfill to proceed. If I, as a player, must defeat the boss, or pull the bathysphere lever, or slide down the flagpole to progress from level 1 to level 2, then I understand the world in a limited, artificial way. Space doesn't exist as a line, nor are our lives composed of a linear sequence of deterministic events; when our gameworlds are arranged this way, the player must be challenged to satisfy their arbitrary win conditions, which in turn requires that they understand the limited rules which constrain the experience. The designer's role is dictatorial, telling the player "here are the conditions that I've decided you must satisfy." The player's inputs test against these pre-determined conditions until they are fulfilled, at which point the designer allows the player to progress. Within this structure, the designer's hand looks something like the following: Creating games without a linear progression structure, and therefore without overt, challenge-based gating goals, allows the player to inhabit the space with a rhythm that better mirrors their own life's than a movie's pacing, as opposed to focusing on artificial pinchpoints that cinch the gameworld's possibility space into a straight line.

Creating games without a linear progression structure, and therefore without overt, challenge-based gating goals, allows the player to inhabit the space with a rhythm that better mirrors their own life's than a movie's pacing, as opposed to focusing on artificial pinchpoints that cinch the gameworld's possibility space into a straight line.

Another offending convention might be a question of where the game's control scheme lives. In character-driven games, the player's inputs most commonly reside in the controller itself, requiring the player to memorize which button does what. The simple fact that the player can only perform actions which are mapped to controller buttons confronts them with the limitations of their role within the world; the player-character is not a 'real person' but a tiny bundle of verbs wandering around the world. Run, jump, punch, shoot, gas, brake, and occasionally a more nuanced context action when they stand in the right spot-- this is the extent of the player's agency. More pointedly, having to memorize button mapping is a ruleset itself, and one that pulls players out of the experience. "How do I jump?" "What does the B button do?" These are concerns that distract from the experience of being there. Alternatively, the game's control scheme might live largely within the simulation itself. If the player's possible interactions lived within the objects in the gameworld instead of within the control pad, the player's range of interactions would only be limited by the extent to which the designer supported them, as opposed to the number of buttons on the controller. Likewise, the more interactions that are drawn out of the gameworld itself, as opposed to being fired into it by the player, the more immersed the player is in the experience of being there, as opposed to the mastery of an ornate control scheme. This control philosophy does not support many games that rely on quick reflexes and life-or-death situations, but perhaps that isn't such a bad thing. One need only look at the success of The Sims and extrapolate its control philosophy outward: each object in the world is filled with unique interactions, resulting in seemingly endless possibilities spread out before the player.

Alternatively, the game's control scheme might live largely within the simulation itself. If the player's possible interactions lived within the objects in the gameworld instead of within the control pad, the player's range of interactions would only be limited by the extent to which the designer supported them, as opposed to the number of buttons on the controller. Likewise, the more interactions that are drawn out of the gameworld itself, as opposed to being fired into it by the player, the more immersed the player is in the experience of being there, as opposed to the mastery of an ornate control scheme. This control philosophy does not support many games that rely on quick reflexes and life-or-death situations, but perhaps that isn't such a bad thing. One need only look at the success of The Sims and extrapolate its control philosophy outward: each object in the world is filled with unique interactions, resulting in seemingly endless possibilities spread out before the player.

A related convention that unduly exposes a game's underlying mechanics results from our need to communicate the player-character's physical state to the player. In many genre games, the player must know his character's current level of health, stamina, and so forth. In real life, one is simply aware of their own physical state; however, since games must communicate relevant information almost entirely through the visuals, we end up with health bars, numerical hitpoint readouts, and pulsing red screen overlays to communicate physical state. The player then is less concerned with their character being 'hurt' or 'in pain' as with their being 'damaged,' like a car or a toy. The rules become transparent: when I lose all my hitpoints I die; when I use a health kit I recover a certain percentage of my hitpoints; I am a box of numbers, as opposed to a real person in a real place. Similar to the prior point, the hitpoint problem presents a limitation native to game genres which rely on combat and life-or-death situations as their core conflicts, as opposed to implying an insurmountable limitation of the medium as a whole. If I am not in danger of being shot, stabbed, bitten or crushed, then I am free to relate to my player-character in human terms instead of numerical status, thus remaining unconscious of the designer's hand.

Similar to the prior point, the hitpoint problem presents a limitation native to game genres which rely on combat and life-or-death situations as their core conflicts, as opposed to implying an insurmountable limitation of the medium as a whole. If I am not in danger of being shot, stabbed, bitten or crushed, then I am free to relate to my player-character in human terms instead of numerical status, thus remaining unconscious of the designer's hand.

All this isn't to say that downplaying the designer's hand is an inherently superior design philosophy; clearly, many of us connect deeply with the conscious interaction between player and machine. But as our industry rides a wave of visual fidelity ever forward, our reliance on game genres tied to the assimilation of concrete rulesets only deepens the schism between player expectations and simulational veracity. It's been posited that games are poised to enter a golden age-- a renaissance, one might say-- and as designers, we might do well to step out of the spotlight, stop obscuring the lens into our simulated worlds, and embrace the virtues of invisibility.

[I'd like to thank Clint Hocking, whose presentation I-fi: Immersive Fidelity in Games informed my thinking.]

8.17.2008

Quick Critique: Braid

[Note that this is a critique of the full game, and contains plot spoilers.]

I am not much of a platformer guy. Except for Mario Galaxy, I haven't really engaged with one in years. Nor am I, since the mid-90's, much of an adventure/puzzle guy, aside from indulging in a few of Telltale's Sam & Max episodes, and of course Portal. Hell I'm not even much of an indie games guy, as something is lost on me in that more abstract realm. But Braid, the new indie puzzle platformer by Jon Blow, grabbed my attention and spoke to me despite my lack of usual interest in the bounds it occupies.

What's most interesting to me about Braid is how it takes familiar mechanics, considers their implications, and then twists them into an effective metaphor expressed through the play itself. Video games it's based off of such as Super Mario Bros. have always pointed towards a cartoon representation of the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics: each of the player's "lives" represent one possible set of decisions Mario might have made; dying and trying again presents a vision of an alternate reality where Mario made a different decision at some crucial point. The one reality that finally leads to the completion of the game is made up only of the lives with which the player made progress past at least one save point, building towards a whole.

Braid takes this interpretive aspect of an existing game format and makes it integral to the overall experience. The player may rewind time at will, throwing the sheer number of alternate realities onscreen into sharp relief. The narrative of the game is expressed through interstitial text relating the story of a man's struggles between maintaining a romantic relationship and pursuing some other, obsessive goal. The seeming regret and misgivings of the protagonist "Tim" in these passages highlights the difference between the endless revision possible in a video game, and the inability to take back permanent life decisions in the real world. The play and the narrative come together to portray the longing and impotence of a man wishing to undo the past. The way the mechanics of the game reinforce this aesthetic theme is wonderfully subtle and fully realized.

The place that this dichotomy falls down is when Blow's reach surpasses his grasp in the epilogue of the game. Mechanical play is well-suited to supporting universal and personal themes such as the ones noted above, and to this end the protagonist's story of love and loss retains meaning when told as a parable. But at the end of the game the narrative content becomes overly weighty and specific, calling out the creation of the atomic bomb and other major scientific and intellectual conundrums by name-- conceptual territory of a fidelity and gravity that the play of Braid can't support. I don't begrudge Blow an attempt at addressing important issues, but the weight of the atomic age seems too much to satisfy with a few lines of text that feel incongruous with the rest of the production. If this aspect of the narrative were going to be present at all, I wanted it reinforced by the gameplay, as the rest of the framing story was; instead, I came away thinking, "Wait, was that supposed to be about the atomic bomb somehow?" This overextension of narrative ambition without satisfactory justification did a disservice to all of the game's other highly successful elements.

As a puzzle game, Braid is nearly flawless. On top of reversability, time works differently in each of the game's worlds, and in each these new mechanics are fully explored. It's a joy to be learning new things along every step of the game. But like most puzzle games, it's a tightly authored experience, with only one solution to any given room: while all the puzzles are set up in extremely clever ways and are largely discoverable to the attentive player on first pass, the puzzles definitely tend away from making the player feel smart for deciphering them and more towards making the player feel like Jon Blow was smart for coming up with them.

To be playable at all, the rules of a game's world must be internally consistent at all times, and Braid is no different. So, the only places that the play of Braid falls down are where Blow breaks his own rules. For instance, it's understood that every puzzle room of Braid is solvable first time through, on its own as a distinct unit. So, when the player must leave a room in World 2 without collecting all the puzzle pieces, then come back later to grab them, it's frustrating and unfair since it's the only place that this rule of Braid's structure isn't upheld. Elsewhere, puzzle solutions require an understanding of the world's properties that haven't been demonstrated up to that point. How am I to know that elements of a completed puzzle can become interactive pieces of the gameworld? Or that an enemy bounces up into the air when it lands on my head? Additional training simply to introduce all the pertinent game dynamics would have reduced the 'unfair' challenge of the game without reducing the fair challenge of figuring out how all those elements fit together to solve a given puzzle. In the end though, these are small quibbles directed towards an outstandingly unique and satisfying puzzle game.

Braid is a brilliant exploration of a principle that Blow has addressed in his prolific conference talks: certain game genres have been prematurely left by the wayside, victims of the ongoing march of technology. There are many formats ripe for reexamination outside the existing assumptions built before they fell out of favor. What if progress in a platformer weren't gated by having to replay segments whenever the player died? What if the challenge weren't in outright manual dexterity and memorization but in mental dexterity and logical deduction? What if the many-worlds quantum aspect of retrying platformer segments were embraced, wound into the play, and made meaningful to the player on multiple levels? What if we went back and picked up design threads that we'd dropped along the way, and found that they still had plenty more slack to explore? It's a way of stepping out of the technological jetstream and embracing a sustainable sort of design that's conscious of more than the medium's here-and-now. One might say it's a method of exploring an alternate path that one branch of game design might have taken, if only we could go back in time and try again.

8.12.2008

Magazine

This month's issue of Official Xbox Magazine (with Fable 2 on the cover) contains a lovely little write-up of 2K Marin (including a team photo where you can see my smilin' mug.) Like the cover says, meet the minds behind BioShock 2! Nice being in print. On newsstands now.

Edit: I just noticed that every single game mentioned on that cover is a sequel.

7.27.2008

Being There

I've been thinking a bit about the strengths of video games as a medium, as well as why I'm drawn to making them. One colors my perception of the other I suppose. But in my estimation every medium has its primary strength.

Literature excels at exploring the internal (psychological, subjective) aspects of a character's personal experiences and memories.

Film excels at conveying narrative via a precisely authored sequence of meaningful moments in time.

And video games excel at fostering the experience of being in a particular place via direct inhabitation of an autonomous agent.

Video games are able to render a place and put the player into it. The meaning of the experience arises from what's contained within the bounds of the gameworld, and the range of possible interactions the player may perform there-- the nouns and the verbs. Just like in real life, where we are and what we can do dictates our present, and our possible futures. Video games provide an alternative to both the where and the what of existence, resulting in simulated alternate life experiences.

It's a powerful thing, to be able to visit another place, to drive the drama onscreen yourself-- not to receive a personal account of someone else's experiences, or observe events as a detached spectator. A modern video game level is a navigable construction of three-dimensional geometry, populated with art and interactivity to convincingly lend it an identity as a believable, inhabitable, living place. At their best, video games transmit to the player the experience of actually being there.

Video games are not a traditional storytelling medium per se. The player is an agent of chaos, making the medium ill-equipped to convey a pre-authored narrative with anywhere near the effectiveness of books or film. Rather, a video game is a box of possibilities, and the best stories told are those that arise from the player expressing his own agency within a functional, believable gameworld. These are player stories, not author stories, and hence they belong to the player himself. Unlike a great film or piece of literature, they don't give the audience an admiration for the genius in someone else's work; they instead supply the potential for genuine personal experience, acts attempted and accomplished by the player as an individual, unique memories that are the player's to own and to pass on. This property is demonstrated when comparing play notes, book club style, with friends-- "what did you do?" versus "here's what I did." While discussing a film or piece of literature runs towards individual interpretation of an identical media artifact, the core experience of playing a video game is itself unique to each player-- an act of realtime media interpretation-- and the most powerful stories told are the ones the player is responsible for. To the player, video games are the most personally meaningful entertainment medium of them all. It is not about the other-- the author, the director. It is about you.

So, the game designer's role is to provide the player with an intriguing place to be, and then give them tools to perform interactions they'd logically be able to as a person in that place-- to fully express their agency within the gameworld that's been provided. In pursuit of these values, the game designer's highest ideal should be verisimilitude of potential experience. The "potential" here is key. Game design is a hands-off kind of shared authorship, and one that requires a lack of ego and a trust in your audience. It's an incredible opportunity we're given: to provide people with new places in which to have new experiences, to give our audience the kind of agency and autonomy they might not have in their daily lives; to create worlds and invite people to play in them.

Kojima has said that game development is a kind of "service industry," and I think I know what he means. It's the same service provided by Philip K. Dick's Rekal, Incorporated: to be transported to places you'd never otherwise visit, to be able to do things you'd never otherwise do. As Ebert says, "video games by their nature require player choices, which is the opposite of the strategy of serious film and literature, which requires authorial control." I'll not be the first to point out that this is an astute observation, and one that highlights their greatest strength: video games at their best abdicate authorial control to the player, and with it shift the locus of the experience from the raw potential onscreen to the hands and mind of the individual. At the end of the day, the play of the game belongs to you. The greatest aspiration of a game designer is merely to set the stage.

[This post was referenced in Jonathan Blow's talk "Games Need You" at this year's Games:EDU South conference in Brighton, England.]

7.13.2008

Japanese: redux

Happy news!

Some time ago, I wrote of my disappointment that Sega was replacing the Japanese voice track in their North American release of Yakuza with a Hollywood voice cast. I ended up playing the full game eventually and did find navigating the world of Yakuza engrossing, but the incongruous voice track left a tarnish on the experience overall.

So, I was excited to read in the current issue of EGM (verified by Sega's official product page) that Yakuza 2's North American release will feature the original Japanese voice track with English subtitles! My guess is that the decision was less artistically-minded than simply pragmatic: I assume that the investment in an English voice cast for the first game didn't pay significant dividends, and with the sequel landing well into the PS2's final hours (not to mention the niche appeal of its subject matter) it's pretty much guaranteed to sell modestly at best. So, market forces and artistic cohesion happen to coincide here, with the most economical production approach resulting in the best end-user experience. Cool. I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

I'm hoping that Yakuza 2 will maintain what was enjoyable about the first game (a Shenmue-like game structure, the exploration of a cohesive and thoroughly foreign gameworld, crunchy melee combat, simple but much-appreciated inventory and RPG elements) and improve its shortcomings (over-frequent and repetitive filler combat sequences, lackluster plot, some janky controls) as well as add a new feature or two (the ability to change Kazuma's outfit perhaps??) Sega suggests a release date of 09/09/08 (9 years after the launch of the Dreamcast-- nice.) Color me psyched!

7.06.2008

Stubborn

Via a link on Jonathan Blow's blog today, I played through lo-fi indie game Flywrench. My clear time was 01:02:53. Which is kind of a miracle, and highlighted something odd about 'hardcore' gamers: we can't help but show computers who's boss.

It's weird! Flywrench is a sadistically difficult game, requiring perfect timing, some luck, and a whole lot of patience. To its designer's credit, the game allows you to instantly retry each time you fail, and fail I did-- hundreds of times certainly within that hour and two minutes, sometimes with infuriating frequency.

But I pushed on, determined, for some reason, to best the machine. The game is balanced and designed well enough that each time I failed, I acknowledged that it was my own fault-- my keypress wasn't precise enough, my analysis of the playfield's current state wasn't accurate enough, my understanding of the physics simulation wasn't clear enough. Each time I failed, even as the droning, dissonant soundtrack squealed in my ears, daring me to quit, my determination to master the inputs and pass the game's challenges grew.

And after an hour and two minutes of frustration and anxiety interrupted occasionally by glimpses of elation, I'd achieved what? I saw the credits. I received a readout of my completion time. I got an error message upon trying to close the executable. And it was over.

The graphics were sterile and abstract, functioning only on the symbolic level. The narrative was mildly surreal and led up to a kind of clever joke, but wasn't even a factor in why I was playing. It was the implicit challenge: man versus machine, me versus a digital, unknowing system of rules that didn't care whether I played it or not. But I had to finish the game, practically out of spite. I was proving to the game itself who was boss, or I guess in actuality I was proving to myself that I could do it. Because really, it was just between me and a bunch of numbers. Intellectually, I know that the game was tuned by a person to be just difficult enough to egg me on, but not quite to the point of being impossible. I was being manipulated. And it worked. I wasn't going to let this game kick my ass.

It's so absurd, I don't even know where the compulsion comes from! It's finishing Super Mario Bros. alone in your room at age 8, or completing some punishing, poorly-designed Sierra adventure on your IBM compatible, or 100-percenting Through the Fire and Flames on Expert. It's beating Contra without the 30 lives code, getting to the kill screen on Donkey Kong, finishing a Metal Gear Solid game without being detected, beating Ninja Gaiden on its hardest difficulty setting (or hell, beating the NES version at all,) or completing The Legend of Zelda without picking up any heart containers.

I can see it from the uninitiated viewer's perspective: why do you put yourself through all this anguish just to complete a video game? It doesn't sound like you're having fun. What's the point? Nobody's going to give you a medal, and it's sure not helping cure cancer. Don't people play games to relax?

I don't have a good answer. I don't know why, when this dumb little game pushed me down and stood over me, squelching its little noises and sending me back to the start of the level, I kept getting back up and trying again. But I did it, and I showed the program I'm better than the best it had to offer.

Why do we feel the need to beat the game? Because it's there.